The village of Aughrim lies 5km west of the town of Ballinasloe in Co. Galway. Aughrim is the site of the infamous battle fought on the 12th of July 1691 between the forces of Jacobite General Charles Chalmot de Saint Rhue and the armies of William of Orange, led by Dutch officer, Godert de Ginkel. The battle had an international dimension as the belligerents were drawn from all over Europe, coming to Ireland to decide who would succeed the English throne. The departure of James to France before the end of the Battle of the Boyne had earned him the name Seamus a cac, or Seamus the shite among the Irish and as the armies arrived to face each other at this decisive battle in Aughrim, William too had departed the theatre of war. The Irish forces must have known that their cause was lost and the best they could do was sue for a peace, a settlement which recognized their religion and secured their status in some way, in this new protestant dominated nation.

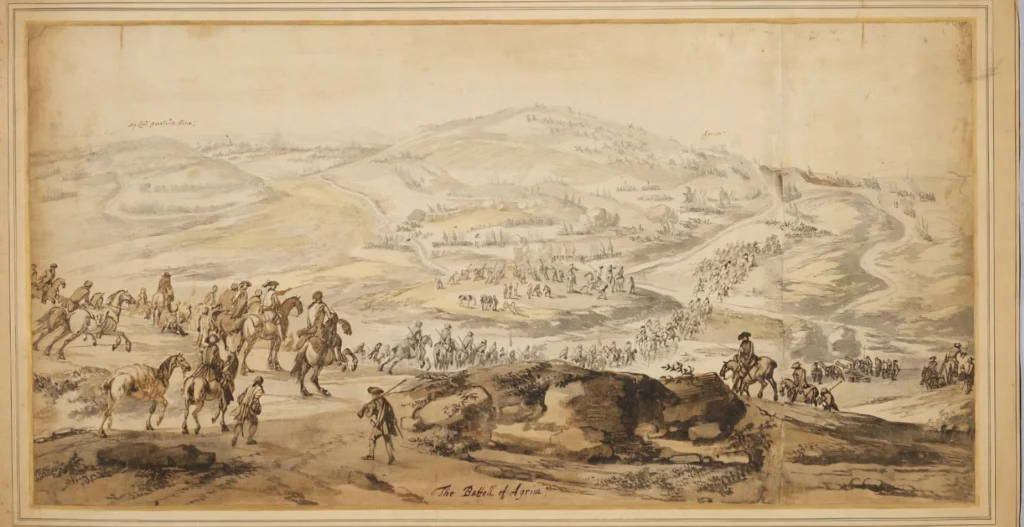

General Saint Ruhe had deployed the bulk of his forces along the crest of Kilmadden Hill with his cavalry on the flank to protect the relatively inexperienced infantry. A heavy mist hung over the battlefield all morning until at 2 o clock in the afternoon when Ginkel’s forces moved into position and began exchanging canon fire for several hours. He then ordered a probing attack to test the Irish forces with the intention of falling back and resuming the battle in the morning. However, the initial skirmish escalated and the Williamite generals argued for an all-out attack. The English and Scottish regiments led by General Mackay attacked the Irish forces on Kilmadden Hill and were soon routed, where upon the Irish forces chased them into boggy ground and clubbed them to death with their muskets. With the right and centre of the Irish formation holding firm, Ginkel attempted to secure the causeway leading to the abandoned Aughrim Castle on the left flank, with his forces succeeding in their third attempt to take the position.

It was at this point a decisive event happened in the battle, as General Saint Ruhe was encouraging his infantry to press on, believing victory was in their grasp, he was exposed to canon fire and was subsequently decapitated. As the sun began to set, the Jacobite army found themselves leaderless and soon the cavalry and dragoon regiments left the field of battle. This was followed by a surrender of the Irish regiment located around the ruins of Aughrim Castle, although the right flank of the Irish forces continued to attack, forcing the French Huguenot regiment into a space which became known ever more as the Bloody Hollow. There a bloody skirmish ensued without a decisive victor. The Irish forces finally broke formation and ran at 9 o’clock as a misty rain fell on the battlefield. They ran into a boggy area towards the rear of Kilmadden Hill, pursued by Ginkel’s cavalry where they were brutally cut down without any quarter being given.

Here is an interesting account of some of the folklore which surround the aftermath. Writing in 1698, eight years after the battle, an Englishman, John Dunton travelling from Dublin to Galway gives this account…

“ Here the River Suck divides the counties of Galway and Roscommon, three miles beyond the town (Ballinasloe) lies Aughrim, an obscure village consisting of a few cabins and an old castle, but now made famous by the defeat of St. Ruth and the Irish Army: the bones of the dead lie yet to be seen would make a man take notice of this place. Tis said the Irish here lost 7,000 men with their whole camp, while the whole loss of the English did not exceed a 1,000. This which I’m very assured of is very strange. After the battle the English did not tarry to bury any of the dead but their own, and left those of the enemy exposed to the fowls of the air, for the country was then so uninhabited that there not hands to inter them. Many dogs resorted to this Aceldama where for want of other food they fed on man’s flesh, and thereby became so dangerous and fierce that a single person could not pass that way without manifest hazard. But a greyhound kept close by the dead body of one who was supposed to have been his master night and day, and though he fed upon corpses with the rest of the dogs, yet he would not allow them nor anything else to touch that which he guarded. When the corpses were all consumed the other dogs departed, but this used to every night to adjacent villages for food and return presently to the where the beloved bones lay, for all the flesh was consumed by putrefaction, and thus he continued from July till January following, when a soldier passing that way near the dog, who perhaps feared a disturbance of what he so carefully watched, he flew upon the soldier, who shot him with his piece”

The story John Dunton relates is a poignant description of the human tragedy surrounding the aftermath of the battle. The true number of deaths are estimated to be around 3,000 on the Irish side making it the bloodiest battle in Irish history. What is even more apparent is the caliber of those who died, the Catholic Irish aristocracy were decimated. The subsequent Treaty of Limerick sought to protect Catholic rights, such as freedom to worship and succession of title. However, for the families of those who had been killed or captured at Aughrim this was not the case, they had their lands swiftly confiscated, never to be returned. The protestant community lit bonfires on the 12th of the July to celebrate the victory at Aughrim, a practice which continued for sixty or more years until England belatedly adopted the Gregorian Calendar. This coincidently had the Battle of the Boyne fall on the 12th of July and was duly adopted by the Protestant community as they began to eulogize King William of Orange even though he had not attended this decisive battle. What is cemented in my mind is a dog laying by his fallen master on a deserted plain in East Galway strewn with corpses and his enduring loyalty in the face of a hopeless situation. What a momentous event that is barely commemorated today! Wild About Ireland Tours.